Yesterday, South Korean President Yoon Suk Yeol declared martial law, absurdly accusing the centre-left opposition parties of collaborating with North Korea to justify suspending constitutional protections, including the right of the National Assembly to meet and discuss. This move faced immediate backlash: opposition lawmakers defied military barricades to convene in the National Assembly, where they unanimously voted to overturn the decree. Facing mounting pressure, including dissent from his own centre-right political party, President Yoon rescinded the martial law order within hours. Pro-democracy norms asserted themselves to ensure that there would be no backsliding into the authoritarianism South Korea suffered from pre-1987. The hapless president now faces calls for his impeachment and expulsion from his own political party. For me, the main takeaway from this episode is the resilience of South Korea’s democratic institutions. South Korea has Western-style political institutions that have been grafted onto its Confucian/East Asian culture in the last few decades. All of this makes me think that inherited culture is less important than social-scientific theories might lead one to suggest. Social scientists, take note! In fact, I think that maybe we should stop using the term “Western” as a short-hand for “liberal democratic countries.”

Here is another take away from the recent events in South Korea. Maybe cultural inheritance and long-term history going back centuries matter even less that Acemoglu and Robinson have suggested. Daron Acemoglu and James A. Robinson, the authors of The Narrow Corridor, were big names even before their recent Nobel Prize. Acemoglu is an economics professor at MIT, known for his work on political economy and development economics. Robinson is a political scientist and economist at the University of Chicago, focusing on political and economic development in Latin America and sub-Saharan Africa. They’ve teamed up before on the bestseller Why Nations Fail, exploring why some countries prosper while others don’t. In The Narrow Corridor, they dive into the delicate balance between state power and societal influence that’s crucial for liberty to flourish. They focus a lot in this book on the Western cultural tradition and, in particular, the Anglo-American/Germanic cultural inheritance. The cover of one version of their book even has images of the ruins of the Parthenon, which communicates that idea that ancient Greeks in the family tree helps to explain why part of the world is democratic while other parts aren’t.

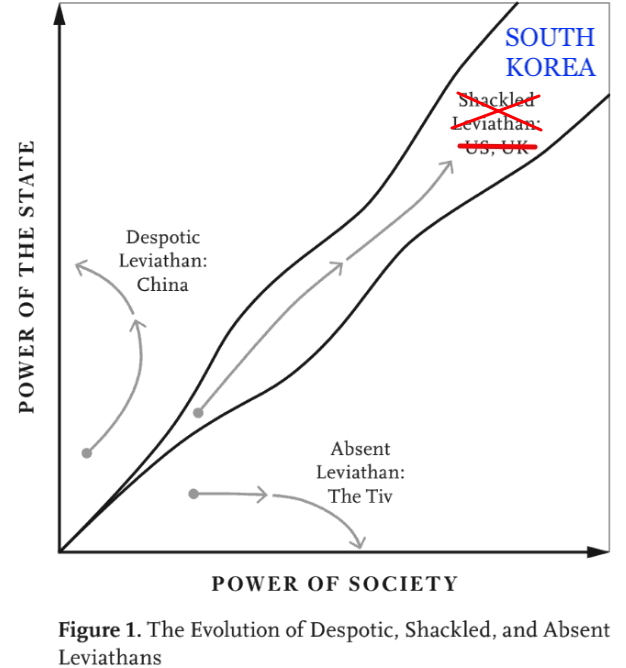

The Narrow Corridor argues that freedom and prosperity thrive when a delicate balance exists between the state and society—a “shackled leviathan.” In these countries (think the UK and the US), strong institutions ensure the state is powerful enough to govern effectively but also constrained by an engaged, organized society that can hold it accountable. In contrast, despotic leviathans have powerful states but weak societies (think China for most of the last thousand years), leading to oppression and authoritarian rule, while absent leviathans suffer from weak states and weak societies, leaving them mired in chaos and lawlessness (think Somalia or most tribal societies). The authors also emphasize that culture plays a huge role—societies don’t just randomly fall into one category or another. Historical events and cultural norms shape their trajectories, creating a kind of “path dependence” that makes it hard to break free from established patterns. That’s sort of true, but that theory makes it harder to explain what recently happened in South Korea. Having lots of Anglo-Saxon “cultural DNA” in a given country seems to matter less to its political institutions than the Narrow Corridor might lead you to believe.

I’m sharing an amusing/thought-provoking image that Pseudoerasmus shared on Twitter/X. The image is a famous figure from the Narrow Corridor that someone hacked yesterday!

Leave a comment